The internal condom gets new life

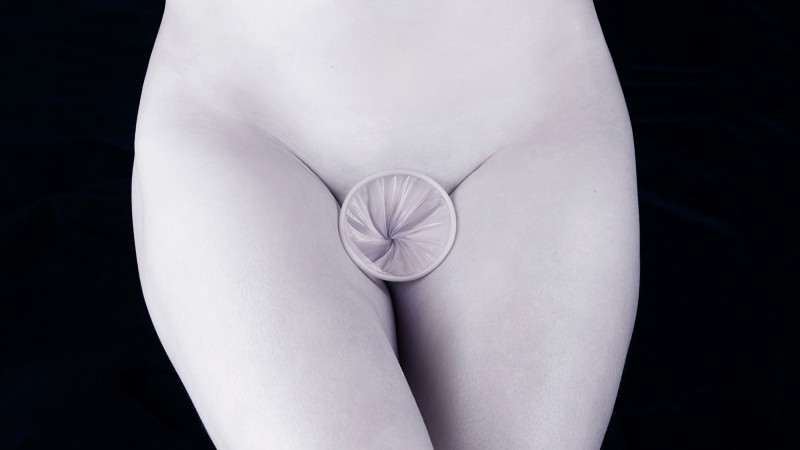

Despite having been on the market for over 20 years, an air of mystery continues to surround the internal condom. Worn internally during sex, this nitrile pouch with a flexible ring at each end can be 95% effective at preventing pregnancy and STIs, yet it remains difficult to find in stores and accounts for only 1.6% of condoms distributed worldwide.

Although commonly known as the “female condom,” the internal condom is used by people of all genders. There are many reasons to love this condom, as blogger and sex educator the Redhead Bedhead has pointed out — it doesn’t require an erection, it’s excellent for period sex, it’s empowering. It can also be a great option during anal sex. This unique contraceptive has the potential to become much more common, but its bumpy start caused misconceptions that plague it to this day.

The internal condom was invented by Danish doctor and inventor Lasse Hessel. Pharmaceutical company Wisconsin Pharmacal bought the rights to the technology in the late 80s, but it took six years for the FDA — which classified the condom as a high-risk class III medical device — to approve it.

When the FC1 internal condom hit the market in 1993, public health experts were thrilled… but consumers weren’t. Focus groups had liked the idea of the condom, but in use, they found it too foreign and confusing. It was also expensive: $5 per condom. As Emily Anthes reports in her detailed history of the condom:

Though some women did eventually come to like the condoms, there was a definite learning curve and as many as one-third to one-half of women had difficulty inserting them. Once in place, the condom had a tendency to squeak or rustle during sex.

The media pounced on these complaints, and utterly skewered the female condom. They ridiculed its aesthetics with seemingly limitless creativity. As sociologist Amy Kaler recounts in her 2004 paper on the condom’s introduction, journalists compared the product to: “a jellyfish, a windsock, a fire hose, a colostomy bag, a Baggie, gumboots, a concertina, a plastic freezer bag, . . . something out of the science-fiction cartoon The Jetsons, a raincoat for a Slinky toy, or a ‘contraption used to punish fallen virgins in the Dark Ages.'”

The barrage of negative press led the crew at Wisconsin Pharmacal to focus their efforts elsewhere. In 1996, they turned toward the global public sector, providing their condoms for at-risk women in low-income countries. Particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, where many women were being diagnosed with HIV, the internal condom made a huge impact.

Encouraged by this response, Wisconsin Pharmacal changed its name to the Female Health Company and made one important alteration to their product: the material. They switched from polyurethane to nitrile, making the condom less noisy and less expensive. This new generation was called the FC2. Between 2007 and 2010, the number of internal condoms distributed globally doubled.

Luckily for us, innovation is everywhere when it comes to modern condoms. Last year, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation awarded $1 million in grants to 11 condom prototypes, including a condom with pull tabs and another which reacts to body heat and conforms to the wearer.

Quite a few internal condom designs are also in the works. An Indian condom company makes the Cupid, which offers internal stability from a foam sponge. The Phoenurse, currently sold in China, comes with an optional insertion stick. The Origami Condom from Los Angeles is made of silicone and unfolds like an accordion when inserted.

Perhaps the most promising and thoroughly researched is the Woman’s Condom, created by global health nonprofit PATH. Starting all the way back in 1998, PATH began consulting focus groups in South Africa, Thailand, Mexico, and the U.S., asking what folks wanted from internal condoms. 300 prototypes later, they hit pay-dirt by implementing a dissolving applicator. The capsule-sized applicator is easily pushed into the vagina, where it releases the full condom pouch. Testers have deemed this condom comfortable, stable, and easy to insert.

But a lot depends on educating the public. There are still myths and confusions surrounding the internal condom that need to be dispelled. We could definitely take a hint from Zimbabwe, Malawi, and Cameroon, where salons and barbershops serve as distribution centers, and Africa, where the condoms are advertised on billboards, TV, and the radio. With the right innovation and advocacy, the internal condom could get the respect it deserves.