Tracking the history of American sex ed films

America’s first sex ed movie was called Damaged Goods. Screened in theaters in 1914, it followed the sad life of a man who contracted syphilis from a sex worker and subsequently committed suicide.

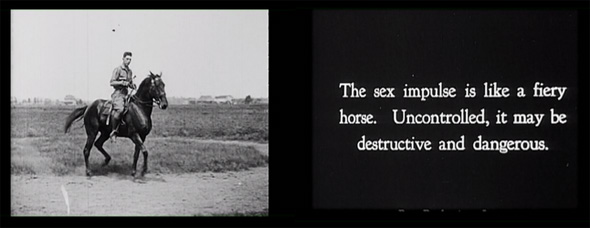

Unsurprisingly, the characters in early sex ed films were stereotypes. Men — whom the films were aimed at — were like stallions, easily overtaken by their sexual urges. Women fell into two categories: harlots out to infect young men with venereal diseases, and virginal “nice girls” with no sexual desire at all.

This account comes to us courtesy of Bitch, where Sarah Mirk has tirelessly deconstructed The Dramatic History of American Sex-Ed Films. In her research, Mirk found an odd and unexpected trajectory:

Instead of becoming steadily better in quality over time, the content, messages, and accuracy of sex-ed films have fluctuated with the moral and political forces of each era. What’s especially surprising in looking at the history of sex-ed films is how the medium has changed in its approach to contraception. Condoms, over time, have gone from being framed as a straightforward way to prevent disease to a failure-prone and risky option.

The first sex ed film to be screened in an American public school was called Human Growth. Funded by a physician and educator who left $500,000 in his will specifically for its creation, the anatomy-focused 20-minute film caused a great stir when it was shown in a seventh grade classroom in Eugene, Oregon in 1948. National magazines even wrote about the event.

The ’60s brought homophobic “stranger danger” public safety movies, then, oddly enough, fearless movies in the ’70s featured full nudity. Contraception made its debut in sex ed films starting in the early ’80s… but the AIDS epidemic quickly cast a dark shadow over the topic.

As the decades went by, films continued to ignore female sexual desire. The clitoris as a pleasurable part of the anatomy was not mentioned until the ’80s, while male masturbation and wet dreams were common topics. Most of the information dispensed to young girls was about menstruation. In fact, Disney once partnered with Kotex to produce an animated short urging girls to “keep smiling and even-tempered” during their periods.

A large shift took place in the 1990s, when the federal government began funding abstinence-only education. Religious groups began visiting schools — they used shame and fear tactics, centering their lessons on morality and virginity. The films made by religious organizations followed the same line of thinking, even including bogus “facts” about condom failure rates. No Second Chance, from 1991, was one of those films:

In the video, a woman extolls students to be abstinent while imagery of a kid playing with a gun rolls onscreen.

“When you use a condom, it’s like playing Russian Roulette. There’s less chance that when you pull the trigger, you’re going to get a bullet in your head,” she tells a class of students. One teen boy pipes up.

“What if I want to have sex before I get married?” he asks.

“Well, I guess you just have to be prepared to die,” she responds.

The upcoming documentary Sex(ED) The Movie (trailer below) estimates that 100,000 sex ed films have been produced in the past century, but the state of American sex ed remains grim. Although 80% of Americans favor comprehensive sex education, only 22 states require sex ed, with only 19 requiring the lessons to be medically accurate. There are no national standards for how sex ed should be taught.

Here in Oregon, where our sex ed policies are considered “progressive,” we’ve updated our sex ed video My Future, My Choice to include gender-neutral language about relationships and a racially diverse cast. But the video strongly recommends abstinence, fails to mention birth control aside from a brief blip about condoms, and, by all accounts, does not address pleasure in the slightest.

We do have the internet, where Scarleteen dispenses accurate and in-depth sex ed information, Laci Green uploads friendly and frank videos, and Go Ask Alice answers an avalanche of questions. But this puts the onus on kids to ask those questions and find the information they need. Films shown in classrooms have an air of authority that the internet will never have. Although we’ve come a long way since Damaged Goods, sex ed films still have room for improvement.