When dildos came out of the closet

In the 1970s, dildos were a point of contention in the feminist movement. A 1974 issue of Lesbian Tide warned: “anyone admitting to using a dildo today would probably be verbally castigated for enjoying ‘phallic’ pleasure.” Some activists thought dildos were too reminiscent of the patriarchy. Others felt that since dildos specifically didn’t require men, using them could actually be a subversive act.

The debate was more about what the dildo represented than precisely how it looked, but looks mattered too. Hyper-realistic vein-ridden dildos were the order of the day, and they tended to emit a strong chemical scent. It would still be a long time before the harms of plasticizers such as phthalates would come to light, but it was obvious that rubber was not the highest quality of dildo materials.

In her thought-provoking piece for Bitch on the early history of silicone dildos, Hallie Lieberman explores not just the feminist debate about the dildo, but also how dildo innovation in the ’70s came from an unlikely place: a humble man named Gosnell Duncan. After becoming paralyzed from the waist down in a workplace accident, Duncan began attending disability conferences and pondering how to enrich his (and others’) sex lives. Conference attendees were intrigued when he mentioned dildos as an option, and so began his journey into dildo-making.

Duncan had a hunch that he could improve upon the dildos of the time, because he was in talks with a chemist at General Electric to formulate the perfect formulation of silicone. Silicone was far more body-safe than rubber: it had no smell, no taste, and wouldn’t melt when exposed to heat — so it could be sterilized between partners. After 9 months of discussion, they discovered the ideal silicone and Duncan began making molds and manufacturing dildos in his basement.

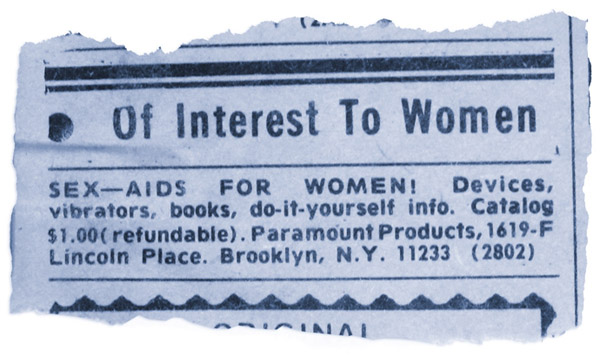

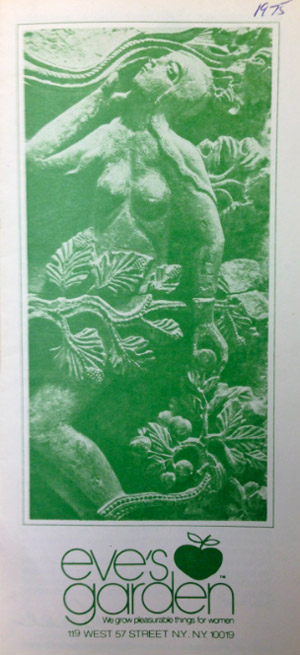

Of course, manufacturing is only half the battle. Marketing was another hurdle. Duncan quickly found that placing ads in disability publications wasn’t enough to keep his business afloat. He renamed his company, from Paramount Therapeutic Products to Scorpio Products, and called up Dell Williams, founder of Eve’s Garden in NYC — the first ever feminist sex toy store.

But Eve’s Garden didn’t stock dildos. Only vibrators.

“Why did a dildo have to look like a cock at all, I asked Duncan,” Williams wrote in her memoir. “Did it have to have a well-defined, blushed-pink head, and blue veins in bas-relief?” Williams wasn’t sure that her customers would buy dildos, no matter what they looked like. But she was willing to find out. She sent out a customer survey asking her patrons what they would want in a dildo. Williams’s customers said that it wasn’t about size, it was about substance: They wanted “something not necessarily large, but definitely tapered. Not particularly wide but undulated at its midsection. Something pliable and easy to care for. Something in a pretty color.”

. . . When he poured his first vat of liquid silicone rubber into a penis-shaped mold, Duncan did not think of his dildo-making as a political act. He was seeking to solve a problem that he, and thousands of other disabled men and their lovers, faced. But in the 1970s dildos were imbued with politics, so to enter the dildo business was to make a political statement. Duncan could have refused to design nonrepresentational dildos in fanciful colors like blue and purple. But he chose to hear Williams out.

So Gosnell Duncan invented, for perhaps the first time, a dildo that represented what women actually wanted. It was called the Venus. Cast in chocolate brown or pink silicone, it resembled a finger — and it was made of a material that wasn’t toxic to the body.

Around that same time, in 1977, Good Vibrations opened in San Francisco. Founder Joani Blank only stocked 2-3 dildos and didn’t display them outright; they were hidden in a plain cabinet in the back. Customers were only shown the cabinet if they asked whether the shop carried “anything else.”

The dildos were brought out permanently in the early 1980s, when Susie Bright began working at the store. Bright was outspoken about dildos, writing in the inaugural edition of her lesbian erotica magazine On Our Backs, “ladies, the discreet, complete, and definitive information on dildos is this: penetration is as heterosexual as kissing!”

In small, feminist sex shops, the conversation around dildos was changing. They were coming out of the closet. And when Bright went to stock the store’s shelves, she knew just who to call: Gosnell Duncan.